A Voyage to Aomori, Part 5 of 5

There are those who claim that happiness has nothing to do with your circumstances, and everything to do with how you choose to respond to them. Such people seem quite numerous nowadays; whether more so than in the past I cannot say.

They are fools.

One does not simply choose to be happy. External circumstances matter. We have created societies that systematically break people. How callous, or plain ignorant, does a person have to be to expect anyone to accept and adapt to a world like that?

And yet, there are places our madness has not yet reached. Places free of arrogance, cruelty, poverty, gender or greed. Places that were there before us and will be there long after us. Places beautiful before anyone was around to corrupt the concept of beauty – a primordial beauty, one we cannot define but know at once when we see it, as though by an instinct as old as love itself.

It was a pain that should not have existed, brought on by the failure of human society, that drove me to Aomori in the distant north of Japan in search of respite. And on my final day there, I found one of the most formidable such places of beauty that I have ever known. It was unexpected – not part of the original plan. And it was guarded by some of the toughest combinations of weather and terrain I have yet encountered.

|

| A location where big explosions once happened bigly. |

But it

was necessary. It was right. For the winds, the rocks, the trees, the

skies, no matter how fierce, how rugged, how sharp, how cold, are not

mad. Never have they hurt out of malice. They exclude and alienate

no-one; all are welcome in their realm. Unlike society's, their

conditions are fair. I could accept them with no hesitation. And in

return for what they take, they give a thousandfold.

They give

better external circumstances. Beautiful circumstances.

Circumstances, if not for happiness, then at least for something

magical and profound; something which speaks to your humanity at a

level our shallow materialist individualisms no longer bother with.

The

Hakkōda

Snow March Disaster

Make no mistake, that does not mean the Hakkoda Mountains will not

kill you if you do not approach them with care. The Aomori Fifth

Infantry Regiment, a unit of the Eighth Division of the Imperial

Japanese Army, learnt this in supremely miserable fashion back in the

New Year of 1902.

Those were tense times. Thirty years since the Meiji Restoration,

Japan's breakneck industrialization and reform had propelled it to

the status of a serious regional power, one of the only countries in

Asia able to stand up to the European empires then devouring the rest

of the continent. However, after brutalizing China in the First

Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan was bullied by a German, Russian and

French triple intervention into giving up the Chinese territory it

had seized in that war – the underlying message being that white

Europeans were a superior race so were allowed to conquer and rob other

countries as they liked, but inferior Asians were not.

Because of course, those countries were not doing this out of concern for the Chinese. The Russians took over instead, setting up a naval base at Port Arthur (Lüshun), spreading troops through Manchuria and developing their influence in Korea – effectively hijacking what the Japanese saw as their own hard-won war gains. This caused them immense frustration and anger, as they knew they were not yet strong enough to fight their European humiliators on even terms. Instead, they resolved to swallow the loss and bide their time, building their strength and preparing for a war with Russia that was now surely inevitable.

That war, they calculated, would take place in the remorseless cold of Manchuria and northern Korea, so the Japanese army regiments stationed in Tohoku were instructed to carry out training for cold conditions, as well as preparing for a hypothesized Russian landing at Hachinohe. Among them was the Fifth Infantry Regiment, who accordingly set out from Aomori City on 23rd January 1902 for a training march across the Hakkōda Mountains.

Because of course, those countries were not doing this out of concern for the Chinese. The Russians took over instead, setting up a naval base at Port Arthur (Lüshun), spreading troops through Manchuria and developing their influence in Korea – effectively hijacking what the Japanese saw as their own hard-won war gains. This caused them immense frustration and anger, as they knew they were not yet strong enough to fight their European humiliators on even terms. Instead, they resolved to swallow the loss and bide their time, building their strength and preparing for a war with Russia that was now surely inevitable.

That war, they calculated, would take place in the remorseless cold of Manchuria and northern Korea, so the Japanese army regiments stationed in Tohoku were instructed to carry out training for cold conditions, as well as preparing for a hypothesized Russian landing at Hachinohe. Among them was the Fifth Infantry Regiment, who accordingly set out from Aomori City on 23rd January 1902 for a training march across the Hakkōda Mountains.

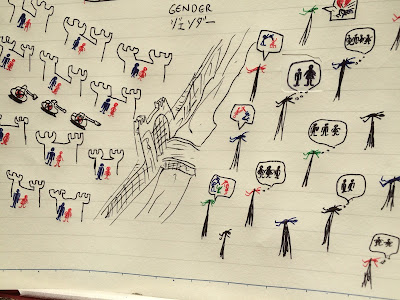

Here you see Aomori Prefecture. Aomori City is in the middle, on the south coast of Mutsu Bay, while Lake Towada can be seen centre south on the prefectural border. The Hakkōdas are the unmissable mass of mountains spreading out across the middle. They are the top end of the great Ōu mountain range, which stretches all the way south through Tohoku.

They are divided into two clumps – the northern and southern groups – and together include over a dozen magnificent Pleistocene stratovolcanoes and lava domes, the southern significantly older than the northern. All their major eruptions were prehistoric, but there are still active hotspots and fissures of volcanic gas – inhalation of which has occasionally killed people in recent years – as well as hot springs of quite some renown, on which more later. The rich volcanic soil has also produced a luxuriant explosion of diverse flora, including rare plants and trees unique to this area, and the way they colour and shape the wetlands, moors and Alpine slopes that roll out in all directions has built the Hakkōdas' repute as one of the most beautiful locations in Japan.

They are also known for their temperamental climate. Look again at

the map, and observe how almost everything west of the Hakkōdas

is flat. What that means is that the ferocious winds of

Siberia roar across the Sea of Japan with no resistance and the

Hakkōdas are the first thing

they hit. The weather can change in moments up there, where the

winds, clouds, snows and rains are not interested in your rules or

your weather forecasts. Never is this more the case than in winter,

and the winter of 1901-2, when the 210 soldiers of the Fifth Infantry

Regiment expedition attempted their crossing of the northern group,

turned out to be one of the harshest ever recorded.

The wind and snow were rough from the start, and by midday the rice and mochi the soldiers were carrying for lunch had frozen. At around 4pm they made it to the ridge at Umatateba, near their first day's objective of the Tashiro hot springs, but had had to abandon their sled of food supplies on the way.

The snowstorm intensified into a furious blizzard. Unable to go on, the soldiers dug a ditch to take shelter. A fuel shortage prevented them from warming themselves or heating their rice. They were stuck in an unprecedented cold wave in which temperatures dropped to -41 ºC. They held out until early dawn the next day, the 24th, whereupon it was decided that they should abandon their original plan and turn back. The merciless weather continued unabating, and in the poor visibility the soldiers lost their way. For the next few days they wandered in circles on the Hakkōdas' northeast slops, struggling through the snow until they collapsed out of cold and hunger.

On January 25th, the third day of the march, the Regiment's headquarters realized something was wrong. A search party set out the next day, finding Corporal Gotō Fusanosuke on the 27th and establishing a headquarters for a large-scale search. It took them four months to account for all members of the expedition. Of the 210 soldiers who had set out on the march, 199 had frozen to death, and most of the 11 survivors had to have arms or legs amputated due to frostbite.

The Hakkōda Snow March Disaster (八甲田雪中行軍遭難事件), as it has become known, is to this day the single deadliest accident in the modern history of mountaineering. It was also a huge scandal for the Japanese army, who granted the victims honours equivalent to war dead in fear that the disaster would ignite public anger against conscription. Funds were collected from officers across Japan to build a bronze memorial to the victims; depicting Corporal Gotō, the first survivor to be found, it was unveiled at Umatateba in 1906 and still stands today.

The wind and snow were rough from the start, and by midday the rice and mochi the soldiers were carrying for lunch had frozen. At around 4pm they made it to the ridge at Umatateba, near their first day's objective of the Tashiro hot springs, but had had to abandon their sled of food supplies on the way.

The snowstorm intensified into a furious blizzard. Unable to go on, the soldiers dug a ditch to take shelter. A fuel shortage prevented them from warming themselves or heating their rice. They were stuck in an unprecedented cold wave in which temperatures dropped to -41 ºC. They held out until early dawn the next day, the 24th, whereupon it was decided that they should abandon their original plan and turn back. The merciless weather continued unabating, and in the poor visibility the soldiers lost their way. For the next few days they wandered in circles on the Hakkōdas' northeast slops, struggling through the snow until they collapsed out of cold and hunger.

On January 25th, the third day of the march, the Regiment's headquarters realized something was wrong. A search party set out the next day, finding Corporal Gotō Fusanosuke on the 27th and establishing a headquarters for a large-scale search. It took them four months to account for all members of the expedition. Of the 210 soldiers who had set out on the march, 199 had frozen to death, and most of the 11 survivors had to have arms or legs amputated due to frostbite.

The Hakkōda Snow March Disaster (八甲田雪中行軍遭難事件), as it has become known, is to this day the single deadliest accident in the modern history of mountaineering. It was also a huge scandal for the Japanese army, who granted the victims honours equivalent to war dead in fear that the disaster would ignite public anger against conscription. Funds were collected from officers across Japan to build a bronze memorial to the victims; depicting Corporal Gotō, the first survivor to be found, it was unveiled at Umatateba in 1906 and still stands today.

|

| The eleven survivors of the Hakkōda Disaster, most with artificial arms or legs, a few months after their rescue. |

Later

on, in 1971, the disaster was popularized when the novelist Jirō

Nitta wrote the documentary novel Death

March on Mount Hakkōda

(八甲田山死の彷徨).

It has since been translated into English and was dramatized in the

1977 movie Mount

Hakkōda;

since then it has continued to spawn texts and film portrayals, the

latest of which was released in 2014. You can find out more about the

disaster first-hand at the Kōbata cemetery in Aomori City, where the

victims were specially interred and where records are still

exhibited.

As for the expected war with Russia, it did indeed take place in 1904-5, and was an event of much greater significance than most history curricula bother to teach people. Japan's crushing victory marked the first defeat of a major European empire by an Asian people in all-out conventional warfare, and was a lightning bolt of inspiration to anti-imperialist struggles across the colonized world. It was also extremely bloody, the first clash between two armies fully equipped with the high-tech machine guns, artillery and other advanced weaponry of the industrial era, killing tens of thousands of people on both sides – not to mention Chinese and Koreans caught in the middle – and foreshadowing the bloodbaths to come in World War I.

The Russian monarchy, held responsible for that country's pain and humiliation, would never recover: it was shaken by revolution that same year and would be done away with in little over a decade. The Japanese too were exhausted by the conflict but felt it had established their place as the dominant power in Asia and an equal to the European empires at last – hence the public outrage and rioting at the restrained peace terms, by which Russia paid no reparations, and only ceded half of Sakhalin to Japan (as opposed to all of it or chunks of the Siberian coastline). This frustrated nationalism and rage at the shameless hypocrisy of Euro-American racism would further feed into Japan's descent into madness in the decades that followed.

The Hakkōdas, however, have wisely stood aloof and apart through all of that business, unsullied by the folly of our kind. And so they still do. They are easier to get into nowadays, certainly; the northern Hakkōdas in particular have become a popular destination for hiking and skiing, with a ropeway up to some more casual walking trails and a network of tougher paths into their wild and spectacular interior. But they are not a place you go for a picnic. As soon as you set foot into their domain, you are left in no doubt that to the will of nature, and not to your artificial rules, is the kingdom, the power and the glory here.

Into the Wind

I decided to climb the Hakkōdas on my last day in Aomori, when a massive storm from Siberia had just attacked Hokkaido and dumped a ton of rain on the region overnight. Its tail was set to batter Aomori through the next day: extreme hurricane-force winds of over 120 km/h were forecast for the mountains that morning, and indeed were no joke even on the streets of Aomori City. The ropeway of course was suspended.

As for the expected war with Russia, it did indeed take place in 1904-5, and was an event of much greater significance than most history curricula bother to teach people. Japan's crushing victory marked the first defeat of a major European empire by an Asian people in all-out conventional warfare, and was a lightning bolt of inspiration to anti-imperialist struggles across the colonized world. It was also extremely bloody, the first clash between two armies fully equipped with the high-tech machine guns, artillery and other advanced weaponry of the industrial era, killing tens of thousands of people on both sides – not to mention Chinese and Koreans caught in the middle – and foreshadowing the bloodbaths to come in World War I.

The Russian monarchy, held responsible for that country's pain and humiliation, would never recover: it was shaken by revolution that same year and would be done away with in little over a decade. The Japanese too were exhausted by the conflict but felt it had established their place as the dominant power in Asia and an equal to the European empires at last – hence the public outrage and rioting at the restrained peace terms, by which Russia paid no reparations, and only ceded half of Sakhalin to Japan (as opposed to all of it or chunks of the Siberian coastline). This frustrated nationalism and rage at the shameless hypocrisy of Euro-American racism would further feed into Japan's descent into madness in the decades that followed.

The Hakkōdas, however, have wisely stood aloof and apart through all of that business, unsullied by the folly of our kind. And so they still do. They are easier to get into nowadays, certainly; the northern Hakkōdas in particular have become a popular destination for hiking and skiing, with a ropeway up to some more casual walking trails and a network of tougher paths into their wild and spectacular interior. But they are not a place you go for a picnic. As soon as you set foot into their domain, you are left in no doubt that to the will of nature, and not to your artificial rules, is the kingdom, the power and the glory here.

Into the Wind

I decided to climb the Hakkōdas on my last day in Aomori, when a massive storm from Siberia had just attacked Hokkaido and dumped a ton of rain on the region overnight. Its tail was set to batter Aomori through the next day: extreme hurricane-force winds of over 120 km/h were forecast for the mountains that morning, and indeed were no joke even on the streets of Aomori City. The ropeway of course was suspended.

You might think I would be hesistant, in those conditions, about heading up a mountain range best known for killing two hundred guys in one go. On the other hand, only limited rain was forecast and visibility was good. I decided to at least take the bus to Sukayu Onsen (酸ヶ湯温泉), a hot spring on the southwest side and one of the main embarkation points for hikers, and see how things looked on site. On arriving there the conditions seemed reasonable enough.

|

| Sukayu Onsen (酸ヶ湯温泉). This is one of Japan's more famous hot springs – more on this later. |

|

| The trailhead. |

|

| The northern Hakkōda group. The main road (red, west side) connects north to Aomori City and south to Lake Towada. Sukayu Onsen (35) is visible at bottom left; the ropeway is centre left. In the top right you can see Tashirotai Marsh; the 1902 Hakkōda Disaster took place on the slopes just northwest of there. |

My

eventual route was to climb the east path from Sukayu Onsen, then to

turn north to the top of Mt. Ōdake (大岳),

the highest peak in the Hakkōdas at 1585m. From there I intended to

cross the next couple of mountains to the north, but the wind made it

too dangerous, so I instead turned west downhill towards the

Kenashitai wetlands, detouring to do a circuit past the upper ropeway

station before descending through the wetlands (along the crack in the

map) back to Sukayu Onsen. It took about six hours in total and was

walkable – just – without any specialist equipment.

The winds were powerful from the beginning, but not too difficult in the early stages. It was somewhat reassuring to see other people also attempting it, and of course each and every one of them was elderly.

For about the first 1-2km the trail was cloaked in rich deciduous forests already breaking out into autumn colours, their leaves literally roaring in the overhead wind.

The winds were powerful from the beginning, but not too difficult in the early stages. It was somewhat reassuring to see other people also attempting it, and of course each and every one of them was elderly.

For about the first 1-2km the trail was cloaked in rich deciduous forests already breaking out into autumn colours, their leaves literally roaring in the overhead wind.

|

| The forest shelters the path except in the odd exposed bit like this, where the wind temporarily gets the chance to trample you. |

Then this rocky gully came into

sight. The path went on to ascend it. That was when things got

interesting.

All of a sudden the wind became

relentless. It seems the shape of this valley channeled it into a

ferocious river of air. The path led up one side then the other,

frequently crossing and plunging everyone straight through the middle

of the onslaught. At one point it became almost impossible to move,

in part because of the wind itself but also because of sheer surprise

at its strength. I pressed on, amidst equivalently marvellous

scenery.

|

| This one was fun. The wind does not show up in the photographs, meaning these images cannot quite replicate what it is like to cross that plank with the wind trying to sumo-wrestle you off it. |

|

| From the other side, you can hunch up amidst the boulders for a breather while watching perplexed people work out how to deal with it and gingerly struggle across one by one. |

|

| The view back down after you've climbed past most of it. |

This was where it became clear

there would be no more shelter from the wind, at all, until the other

side of the mountains. It was as though these upper slopes penetrated

into the elemental plane of air itself, a realm where the wind held

absolute sway and all beneath was at its mercy.

It heralded a change in the terrain, too. The forests gave way to marshland, and the trees to shorter and hardier shrubs. The snow lasts until July up here, preventing tall trees from growing.

It heralded a change in the terrain, too. The forests gave way to marshland, and the trees to shorter and hardier shrubs. The snow lasts until July up here, preventing tall trees from growing.

Then you reach Sennintai

(仙人袋),

the “hermit's mountain”. This is a small plateau with a three-way

junction: the east path goes down to Tashirotai, while the north path

takes you deeper into the mountains.

Apparently this area used to be a much larger swamp, although you still find rare frogs and newts in the ponds that remain. The ecology up here is very unique thanks to the sulphurous earth and volatile weather.

Apparently this area used to be a much larger swamp, although you still find rare frogs and newts in the ponds that remain. The ecology up here is very unique thanks to the sulphurous earth and volatile weather.

As planned I took the north path,

towards the principal peak of Ōdake (大岳).

How wonderful the weather looks in these photos, which do not capture

the sensation of the wind beating you up nor its deafening roar as it

does so.

On the final approach to the

summit the wind grew more violent than ever. It looked all green and

meadowy from further away, but once on it it was far more reminiscent

of Mount

Fuji: a rockscape of volcanic reds and browns, steep enough

to force you onto all fours, and fully exposed to bitterly cold winds

even stronger perhaps than on Japan's highest mountain

that day.

If there was a forgiving side to

the wind, it was that it was coming from the northwest; and climbing

up from the south, the shape of the terrain meant the wind was trying

to push you into the mountain rather than off it. There are

few photos from this part because I was mainly focused on getting

through it without a calamity. The real challenge was the group of

hikers in front of me whom the wind had slowed to a literal crawl,

and whenever they stopped I could do little but wait at the back,

unsheltered and ever so slightly exasperated. There are chains to

hold onto in the final bit, and one does hold onto them no matter

what.

On seeing this, it was like all

the adrenaline just exploded – a sensation I cannot capture in

words, a burst of supreme relief and accomplishment even while

acknowledging that the true supremacy was the wind's. Here on the

summit of Ōdake it was the mightiest I have known it anywhere, so strong you cannot stand straight in it and frigidly

cold. It was glorious.

|

| The view north from the Ōdake summit. That bump on the ridge (centre) is the upper ropeway station. Aomori City is faint but visible in the distance. |

In a few moments it became my concern to get off that summit as swiftly as

possible. Descending on its opposite side, the north, grants you the

welcome sight of a mountain hut on the shoulder between Ōdake and

the peaks further along. The wind did not relent, and by now I had

sustained about two hours of it without pause, so I scrambled down to

the hut as fast as was safely feasible.

|

| North from Ōdake. Idodake (井戸だけ) is ahead with its distinctive crater. The Ōdake refuge hut sits in between. |

This hut was to provide one of

the more surreal episodes in my experience of hiking in Japanese

mountains. After staggering for an age through this near-deserted

wilderness of remorseless wind and cold, you might imagine my

surprise when I hauled open the sliding door to find the hut

absolutely packed to the walls with some thirty or forty elderly

hikers. They were in the heartiest of spirits, chatting and laughing

as though at some party or casual reception, as they energetically

did up their jackets and backpacks and prepared to make off in

goodness knows which direction. I waited in the entrance as they

filed past, each one happily begging my pardon as they might in the

crowds of a Tokyo festival.

Then they were gone, and the hut was as a ghost house a million miles from everywhere. It started to rain. I sat alone inside and took my lunch, listening to the bellowing wind and rain attempting to rattle down the whole wooden structure and wondering what the heck I just saw.

Fortunately the rain was only a passing shower, although there was no change in the wind when I stepped outside.

My original plan had been to continue on up the northern peaks of Itodake (井戸岳) and Akakuradake (赤倉岳): that is, up the stairs on the right in this picture.

Then they were gone, and the hut was as a ghost house a million miles from everywhere. It started to rain. I sat alone inside and took my lunch, listening to the bellowing wind and rain attempting to rattle down the whole wooden structure and wondering what the heck I just saw.

Fortunately the rain was only a passing shower, although there was no change in the wind when I stepped outside.

My original plan had been to continue on up the northern peaks of Itodake (井戸岳) and Akakuradake (赤倉岳): that is, up the stairs on the right in this picture.

Already cold and exhausted, I

could see from there that there were no barriers or shelter up on

that totally exposed ascent. The wind was steamrolling down from the

west, perpendicular to the stairs. After just a few seconds of

looking at it, I thought: no.

So instead I turned west, down the valley towards the Kenashitai wetlands. This meant that the wind was coming at me from in front for the first time that day. It was a matter of physically wrestling with it for every step forward, and hoping dearly that it would not continue like that all the way down.

So instead I turned west, down the valley towards the Kenashitai wetlands. This meant that the wind was coming at me from in front for the first time that day. It was a matter of physically wrestling with it for every step forward, and hoping dearly that it would not continue like that all the way down.

Fortunately it did not, and soon

the path went low enough for the trees to start growing again,

providing at last some breaks in the wind. Still the gales put the

leaves and branches in a continuous roar that drowned out all other

sounds.

|

| Looking back east at the northern Hakkōdas' main series of peaks. From right to left: Ōdake, Itodake and Akakuradake. |

About halfway to the wetlands

there is a junction, where a path leads north to the ridge with the

upper ropeway station. Having been deprived of the opportunity to do

the full hike across the peaks, and still with plenty of hours in the

day, I decided at least to explore that way before returning

here to finish the descent.

Not surprisingly the ropeway

station was shut: the wind had suspended the car itself and no-one

had come up this way today. That meant I had this entire outer ridge

to myself.

As the

northernmost point in the heights of the Hakkōda range, this is also

where you find its best views over Aomori

City.

You probably want to be sane and come up when the ropeway is working,

and actually lets you indoors to the observation deck with its coffee

and central heating, unlike this.

|

| Aomori City from next to the ropeway station. Not a day of crisp clear skies, but still good enough to see as far as the boats in Mutsu Bay. In better visibility you can see as far as the Shimokita Peninsula from here. |

|

| A good vantage point on the A-shapes of the Aomori Bay Bridge and the ASPAM building. |

The ropeway

ridge's paths are much gentler than the true hiking trails further

in. A figure-of-eight route winds around its marshlands, offering

some good views and a signboard-assisted immersion in the Hakkōdas'

peculiar flora and fauna. When the air is in a calmer mood it

probably gets a bit lively with families or school groups up here.

This is also the home of the fabled “snow monsters”: a very rare phenomenon that you only get in places where the conditions are exactly right. Parts of this ridge sport dense-leaved conifer trees, and from January to March they are covered in heavy snow and ice, packed by the powerful wind into ominous standing shapes.

This is also the home of the fabled “snow monsters”: a very rare phenomenon that you only get in places where the conditions are exactly right. Parts of this ridge sport dense-leaved conifer trees, and from January to March they are covered in heavy snow and ice, packed by the powerful wind into ominous standing shapes.

|

| The view south, across the western slopes of the northern Hakkōdas. The Kenashitai wetlands are the lower yellowy area on the right. |

|

| The peak of Ōdake, once again looking so gentle from further away. |

After a more

relaxed (yet still unremittingly windy) stroll compared to the

earlier ordeal, I returned to the lower fork and continued down

towards the wetlands of Kenashitai

(毛無袋)

(which means "hairless plain") on the mountains' western flanks. The upper marshes are a wide-open

space with some lovely unfurling views all around. The wind was still

strong, but more rawr-rawr-bear strong rather than

artillery-in-the-face strong like on the peaks.

|

| Upper Kenashitai. |

|

| The water in this marsh is startlingly clear. |

|

| The view back east towards the peaks, lit up by the clearing clouds. |

The shrubs become more colourful

as you reach the end of the upper section, at which point you enter a

forested barrier that separates upper and lower Kenashitai. It is as

though after the trek across the marshes, the mountains drop a

curtain of denser growth to build your suspense – for as it

unfurls, a miracle rolls out below.

To look across

lower Kenashitai is to behold one of those supreme marvels of nature

that is not so much seen as experienced. That is, sensed with the full extent of your psyche; something that

electrifies every cell in your body and connects you straight back to

the elemental stuff of the stars from which you and all of this

planet came. No telling of it afterwards can replicate it, so I will

not do it the disrespect of trying. I will say only that I remember

no other sight in my life at which the impulse was literally to

scream from the shock of its staggering beauty.

A narrow

stairway-to-heaven leads down into this painted landscape, the

consummation of a day of utter catharsis.

And alas (or thank goodness,

depending how much it killed you), at the end of the wetlands the

trail dips down, through a final patch of forest, and returns at last

to Sukayu Onsen.

Doing it in those conditions was

arguably insane. But it was also a once-in-a-lifetime experience,

necessary in the circumstances, one of the only things strong enough

to beat back the tides of human society's far more excruciating

insanity for at least a few days thereafter. The mountains may be

harsh, but unlike humanity they still bother to be fair. Go prepared

and they will reward you with kindness, respect, and wonders you

might find nowhere else.

Sukayu Onsen and the “Thousand-People Bath”

Sukayu Onsen and the “Thousand-People Bath”

We

cannot round off a look at the Hakkōda Mountains without some

attention to these Sukayu

Hot Springs (酸ヶ湯温泉).

This

onsen

is one of the most famous in Japan. It has been taking its sulphurous

water straight from the volcanism of the northern Hakkōdas for over

three hundred years in one of the snowiest inhabited sites on Earth,

and stands as a magical oasis for anyone who has spent the day

struggling through this region's winds and snows.

The onsen comes with a fully-equipped inn, and many people come specifically to stay in it as a mountain resort. The hot springs themselves are distinct in that the main baths do not segregate men and women. This is mixed bathing (kon'yoku), in the traditional Japanese style, although there are also separate male-only and female-only baths for those who prefer it that way.

The most celebrated of these baths is the so-called sennin-buro (千人風呂), literally the 'thousand-people bath': a very large beech wood affair that is often featured on television.

The onsen comes with a fully-equipped inn, and many people come specifically to stay in it as a mountain resort. The hot springs themselves are distinct in that the main baths do not segregate men and women. This is mixed bathing (kon'yoku), in the traditional Japanese style, although there are also separate male-only and female-only baths for those who prefer it that way.

The most celebrated of these baths is the so-called sennin-buro (千人風呂), literally the 'thousand-people bath': a very large beech wood affair that is often featured on television.

|

| Whether it can in fact fit a thousand people, and whether the people in such a circumstance would actually enjoy it, is a matter beyond my expertise. |

A very reasonable 1000 yen gets

you a rented towel and access to the baths and rest area. After the

trials by wind that day, these hot springs brought a relief that

cannot be overstated. They also marked the end to a week of the

freshness and profundity of northernmost Japan, for after the return

to Aomori City and a final go at its scallops, it was back to the

broken realities of Tokyo the following day.

As

some of the articles mixed in with this series suggest,

terrible things took place not long after I left Aomori on that

overcast October morning. 2015 was the year when I learnt first-hand

the infinite reach

of human cruelty:

that no matter where on this Earth I go, there is no respite from the

coldness and arrogance with which not outlying villains but people

in mainstream society

butcher the souls of anyone they deem to be different. It was the year I

learnt the depth of humanity's corrupted determination to be a race that

leaves people behind; and that love and friendship, let alone

kindness, have been bled from its world altogether.

I

will not pretend that these memories of Aomori have helped to ease

the pain. Nonetheless, they are special in their own way. The

windswept coasts of Shimokita;

the sulphur and stone of Osorezan;

the fresh streets and echoing heritage of Aomori

City;

the tense tranquility of Lake

Towada;

and above all, perhaps, that roaring catharsis atop the Hakkōda

mountains: at the time of my worst distress in a decade, it was only

in the very earth, the seas, the skies of these places that I found a

peace, a warmth, and yes, a love – even when virtually every last one

of you human sods, with your walls and judgementalism, went out of

your way to look upon my wretched writhing shipwreck of a life and

deny me yours.

I shall devote the rest of my

time amongst you, you humans, to breaking down your walls and

wringing your contempt for love from your twisted hides. Whether you

want it or not, one day you shall care for each other. One day you

shall love.

I no longer know any gentler way to put it. That itself brings me a grief I cannot convey. But the plain fact is that thirty years of your endless walls and spikes, a lifetime of neverending alienation and loneliness have taken their toll, and in spite of all your insistences to the contrary, that pain is not a thing one can just choose to cover up and smile.

Yes: one day this world will be a place of love. I swear it. But even if I am far away by then, as is most likely, I may still carry these memories of the retreat to Aomori, where I found places to peer through your centuries of illusions and glimpse a world of strong love; beautiful love. Love that in spite of everything you do to deny and violate it, has always been, and will always be, this planet's essence and destiny.

Let the winds rage as they please.

I no longer know any gentler way to put it. That itself brings me a grief I cannot convey. But the plain fact is that thirty years of your endless walls and spikes, a lifetime of neverending alienation and loneliness have taken their toll, and in spite of all your insistences to the contrary, that pain is not a thing one can just choose to cover up and smile.

Yes: one day this world will be a place of love. I swear it. But even if I am far away by then, as is most likely, I may still carry these memories of the retreat to Aomori, where I found places to peer through your centuries of illusions and glimpse a world of strong love; beautiful love. Love that in spite of everything you do to deny and violate it, has always been, and will always be, this planet's essence and destiny.

Let the winds rage as they please.

1)

THE

SHIMOKITA PENINSULA

– A

Bridge Between Worlds

2) OSOREZAN – Mount Fear

3) AOMORI CITY – Rassera, Rassera: The Story of the North

4) OIRASE GORGE and LAKE TOWADA – Colourfully Lurking

2) OSOREZAN – Mount Fear

3) AOMORI CITY – Rassera, Rassera: The Story of the North

4) OIRASE GORGE and LAKE TOWADA – Colourfully Lurking

No comments:

Post a Comment